Frances Watts

Frances Watts is the pen-name of Ali Lavau, a Swiss born Australian author, who moved to Sydney when she was three years old. She studied English Literature at Macquarie University in Sydney, before teaching Australian Literature and children's literature. She went on to complete a PhD and took her first job in publishing. For ten years she worked with many talented Australian children’s authors and illustrators before she began writing her own books. Her delightful first picture book Kisses for Daddy (2005), which was illustrated by David Legge, was an immediate success. Her second picture book, also with David Legge, was the wonderful and innovative non-fiction book Parsley Rabbit’s Book about Books (2007). This won the Children’s Book Council of Australia’s Eve Pownall Award. Since then her writing has kicked into overdrive, with a number of wonderful books and a prolific output. I have listed all of Frances Watts' books at the end of this post.

The Sword Girl Series

This is an exciting series of books by Frances Watts that is illustrated by Kate Greenaway Medal winner

Gregory Rogers. The central character is Tommy (short for Thomasina) who is a feisty kitchen hand who longs to

be a knight. When Tommy, through a series of unusual events, is finally promoted to Keeper of the Blades,

her life changes. As Frances Watts shares in her interview responses below, Tommy is "a girl who wasn’t a princess or a fairy, who could be kind and

thoughtful and empathetic yet still be active and adventurous and

ambitious". This is the perfect book series for girls who love adventure, action and want an

alternative to stereotypical books for girls. One of my grandchildren (Rebecca) is just such an independent, intelligent, and creative girl of seven, who loves complex characters who don't follow the crowd. She has been reading these books as they have been released and just loves them. But the appeal of the books will be wider than simply girls, many boys will enjoy these fast moving and enjoyable tales with action and interest from beginning to end. They are ideally suited for young independent readers aged 6-9 years. The RRP in Australia is $11.99 for each book.

'The Secret of the Swords' (2012), illustrated by Gregory RogersTommy is a kitchen hand at Flamant Castle who dreams of just one thing, becoming a knight! One day through fate or good fortune, she finds herself defending a cat, then herself, with just a broom from the blows of a boy who is the keeper of the knights' swords. When she is made the Keeper of the Blades, caring for all the swords in the castle armoury, it seems like her dreams might have come true. But after some discoveries about the cat, and then some more about the swords, Sir Walter's most valuable sword goes missing from the sword room. Disaster beckons. Question is, will Tommy be able to find it before she is sent back to the kitchen in disgrace?

'The Poison Plot' (2012), illustrated by Gregory Rogers, Allen & Unwin, 2012

This is the second adventure in the 'Sword Girl' series. Evil plans are stirring and it's up to Tommy

to keep the peace at Flamant Castle! Tommy is on an errand to the smithy in the town, and overhears a

plot to poison Sir Walter the Bald, the castle's bravest knight. It is to occur during a banquet and it is to look like the

work of a neighbouring nobleman. Tommy must foil the plot or Flamant

Castle will be at war. As in the first story in the series, Tommy receives some help from some unusual sources.

'Tournament Trouble' (2012), illustrated by Gregory Rogers

Flamant Castle is having a tournament and all the knights and squires of the neighbouring Roses Castle are invited. Tommy has jobs to do at Flamant and looks set to miss the fun and excitement. After Edward the Squire falls from his horse it looks as if Flamant Castle will be a squire short. Sir Benedict asks Tommy to take his place and offers her one of his own horses. But there's a problem, she has never ridden a horse before, and even if she could, there would be jousting to learn. With some unexpected help with her riding she sets out to help Flamant win the tournament.

'The Siege Scare' (2012), illustrated by Gregory Rogers

An Interview with Frances Watts

1. TC: What contributed most to your love of story in your childhood years?

FW: Probably a plentiful supply of good books! My parents were (and are) avid readers, and my sister and I just naturally followed in their footsteps. We were regulars at the local library and the second-hand book store, and my grandparents in America used to send huge parcels of books and subscriptions to children’s magazines. (I particularly remember Cricket, which was essentially a literary magazine for kids.)

But you asked about my love of story particularly. I think I’ve always been drawn to story because to read a story is not just to observe, to be a spectator; it is to feel, to live, to experience. As Atticus Finch said in To Kill a Mockingbird, one of the most wonderful books of all: You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view—until you climb into his skin and walk around in it. The intimacy of a story can provide that experience. When you read, it is personal: good literature takes you right out of your own skin and into someone else’s. It has a voice that rings true. It makes you feel something.

2. TC: Could you tell me a little about the inspiration for the Sword Girl series?

|

| Château de Chillon (Wiki Commons) |

3. TC: Thomasina is obviously an unusual lead character in a children's book set in medieval times. Is the choice all about simply wanting to portray a girl as a strong, clever, courageous and determined lead character, or are there other reasons for this interesting character?

FW: Yes, being able to write a strong girl character was definitely something I wanted to do—a girl who wasn’t a princess or a fairy, who could be kind and thoughtful and empathetic yet still be active and adventurous and ambitious. I think, too, that I wanted to convey the idea that the times we live in can change, can be changed – but it is up to us to change them, to help to make the world we want to live in. And sometimes that’s just a matter of being yourself and following your heart. As Tommy performs her role as Keeper of the Blades with such diligence and skill and determination, more and more people around her begin to accept the idea of her one day becoming a knight.

4. TC: Do you have any particular reasons for pitching this book series at young independent readers?

FW: It’s an age group I do enjoy writing for. There’s a combination of innocence and awareness; young readers embrace characters wholeheartedly, they get a kick out of absurd humour and they are absolutely open to joy and wonder. In a way, though, I never feel like I’m deliberately pitching my books at a particular age group or ‘market’; in the first instance, I just write the stories I want to tell and worry about the audience later.

5. TC: You've obviously done some research in situating these stories historically, but you also have fun with names and language and a variety of elements of fantasy. How and why did you come up with this interesting mix?

FW: I love language—its quirks, its ambiguities, the way it sounds, the way we can play with it; there’s always an element of play with language in my writing, just because it’s a passion of mine. (And, if I’m honest, I’m writing for myself first, before any other reader.) As for those elements of fantasy…I just can’t explain them! It’s what comes out when I begin to write.

6. TC: What is the best response you've ever had to a book?

FW: I

don’t know if I could choose a single instance: any time I hear that

someone has enjoyed one of my books, has connected with the characters,

has been moved or delighted or inspired, is a thrill. But one of the

most moving ‘uses’ of one of my books has to be when 'Kisses for Daddy'

was chosen, for a while, by the Storybook Dads program Dartmoor prison

in the UK. The program helps inmates to record bedtime stories onto CDs

and DVDs. These are then sent to their children, helping prisoner

parents to maintain an emotional bond with their children. I was lucky

enough to hear a recording of a prisoner reading Kisses for Daddy to his

son. Some of the prisoners have poor literacy skills themselves, but

are keen to encourage their own children to read. For a book to become a

means of a father expressing his love for his children, and his hopes

for their future, is a beautiful thing.

FW: I

don’t know if I could choose a single instance: any time I hear that

someone has enjoyed one of my books, has connected with the characters,

has been moved or delighted or inspired, is a thrill. But one of the

most moving ‘uses’ of one of my books has to be when 'Kisses for Daddy'

was chosen, for a while, by the Storybook Dads program Dartmoor prison

in the UK. The program helps inmates to record bedtime stories onto CDs

and DVDs. These are then sent to their children, helping prisoner

parents to maintain an emotional bond with their children. I was lucky

enough to hear a recording of a prisoner reading Kisses for Daddy to his

son. Some of the prisoners have poor literacy skills themselves, but

are keen to encourage their own children to read. For a book to become a

means of a father expressing his love for his children, and his hopes

for their future, is a beautiful thing.7. TC: Will there be lots more Sword Girl books?

FW: I hope so. I’m having a lot of fun with the characters and the setting. I’ve just finished writing the sixth book (books 5 and 6 in the series, ' The Terrible Trickster' and 'Pigeon Problems', will be published in April 2013) and I still feel like I’m bursting with ideas.

8. TC: On a long haul flight to London, which two books would you take?

FW: Hmmm...That’s a very different question to the whole ‘desert island’ concept, because I’m not going to be taking favourite books on that flight but ones I haven’t read yet. So these aren’t recommendations but, rather, books I’m keen to read myself. I’ve just started Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue—he’s a dazzling writer. And if we can delay the flight till November I’m really looking forward to getting my hands on Barbara Kingsolver’s new novel, Flight Behaviour. She has a voice that really gets into my head.

Other Books by Frances Watts

'Kisses for Daddy' (illus. David Legge) (2005)

'Parsley Rabbit's Book about Books' (2007)

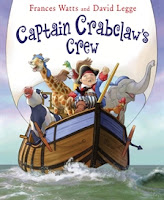

'Captain Crabclaw's Crew' (2009)

Ernie & Maud Series

A series of junior novels about two very unlikely superheroes, Extraordinary Ernie and Marvellous Maud.

'Extraordinary Ernie & Marvellous Maud' (2009), illustrated by Judy Watson. CBC Notable Book in 2009.

'The Greatest Sheep in History' (2009) illustrated by Judy Watson

'The Middle Sheep' (2011), illustrated by Judy Watson

'Heroes of the Year' (2012), illustrated by Judy Watson

Gerander Trilogy

'The Song of the Winns' (2011). Children’s Book Council of Australia Notable Book 2011.

'The Spies of Gerander' (2011)

'The Secret of Zanzibar' (2012)

Picture Books

'Kisses for Daddy' (2006), illustrated by David Legge. Children’s Book Council of Australia Honour Book, 2006

'Parsley Rabbit’s Book about Books' (2007), illustrated by David Legge. Winner of the Children’s Book Council of Australia Book of the Year: Eve Pownall Award, 2008.

'Captain Crabclaw’s Crew' (2008), illustrated by David Legge. Shortlisted REAL children’s choice awards (NSW, Vic, ACT, NT) 2012. Children’s Book Council of Australia Notable Book 2010.

'A Rat in a Stripy Sock' (2010), illustrated by David Francis. Shortlisted REAL children’s choice awards (NSW, Vic, ACT, NT) 2012. Children’s Book Council of Australia Notable Book 2011.

'Goodnight, Mice!' (2011), illustrated by Judy Watson. Winner: Prime Minister’s Literary Award 2012. Children’s Book Council of Australia Notable Book 2012.

For more information on Frances Watts and her work (HERE)