Above: Two children reading together

While there were some reasonable grounds for supporting the traditional order, including the young child's difficulty physically handling pencils to create letters and words, more limited hand eye coordination etc, we accept now that it was simplistic to assume that there needed to be a lock step developmental sequence for spoken and written language.

We also know, there are good reasons (and evidence) to support the early introduction of writing early (and some of us spent many years making this point). For example, while educators, psychologists and paediatricians once assumed there is little communicative intent with a newborn baby, it's clear that almost from the first day of life, babies begin to respond to their world. And many of their very early vocalisations, eye movements, gazes, facial movements and body movements are attempts to communicate. I'm a bit of a baby whisperer myself, and can get smiles from babies very early (and NO older readers, it isn't 'wind'!!).

Well known paediatrician Dr Kim Oates gave a wonderful lecture on this topic at New College in 2006 as part of the New College Lecture series (that at the time I hosted here). While speaking follows well after the ability to hear and respond to sound, attempts to communicate commence almost immediately. Babies will begin to focus their eyes on objects, and particularly faces talking to them VERY early.

|

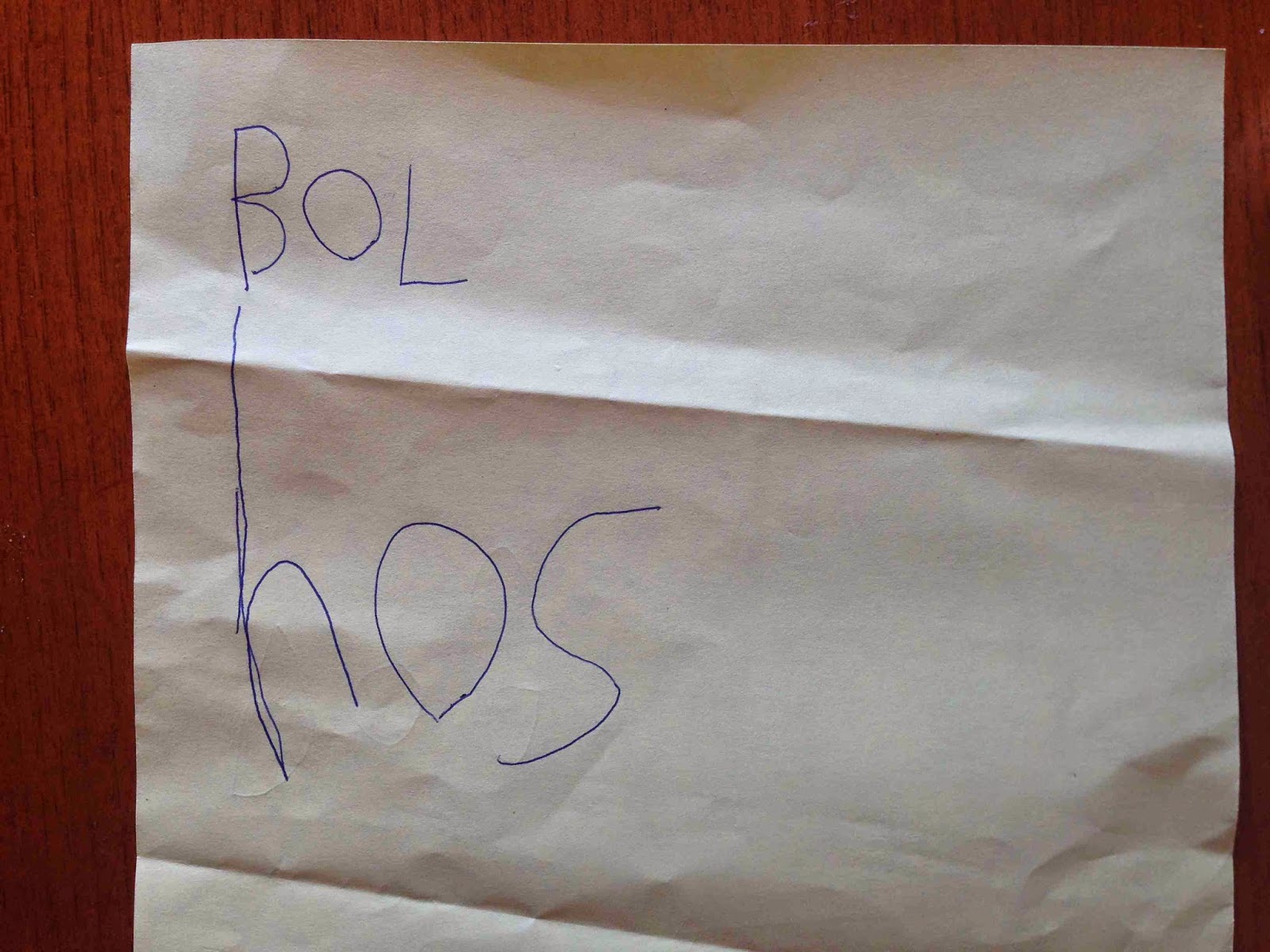

| Lydia writing at Palace of Versailles |

Any as for writing, parents will attest to the marks small children will make on floors, walls and paper if they get hold of a crayon of pencil! Children begin attempting to place their mark on the world as soon as they can grab anything that will make a mark. It's as if they want to be able to say:

"Look, I did this. This is MY mark."

And of course, if you ask older toddlers what it says, they will often say things like, "me and mummy", "It's just a word", "it's a drawing", "dog" etc.

What do we know about early scribble and drawing?

We

now know that even children's earliest scribbles very quickly have meaning associated with them. While at first children are as much

interested in the gross motor movement (the rhythmic drawing of circular

patterns, fast scribble to fill a page etc), they soon begin to attempt

much more, as they seek to communicate or create meaning through their

scribbles, patterns and drawing.

There have been numerous studies of children's early art, and many

examined early literacy prior to the 1970s, but few looked closely at the relationship between

the two. A colleague and dear friend of mine (still!) from Indiana University, Professor Jerome C. Harste conducted significant research in the late 1970s and early 1980s that

taught us much about children's early writing. With his colleagues

Professors Virginia Woodward and Carolyn Burke and many graduate

students, they studied the early writing of children aged 3, 4, 5 & 6

years. They concluded that the process of

scribbling "bears sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic similarity" to the processes we observe in reading and writing [See Harste, Woodward & Burke (1983), Language Stories and Literacy Lessons.

Harste, Woodward and Burke concluded that most children know the

difference between reading and writing by age 3, and by this time

they are developing an understanding of written language, demonstrated

in their scribbles and attempts to write and draw. They argued against traditional developmental notions and suggested from at least the age of 3, children begin to demonstrate elements of authoring. They named this the "authoring cycle". As they examined the early

'scribble' and 'writing' of very young children they identified:

- Organization (evidence of conventions and the genesis of cognitive processes similar to adults)

- Intentionality (evidence children knew their marks signify something)

- Generativeness (an attempt to generate or make meaning)

- Risk-taking (trying things they hadn't before)

- Awareness that writing & language have social functions

- Understanding that context matters in language (i.e. the situation is related to what you write and how you use it)

- Meaning making in children's 'scribbles', and later words using invented spelling, that formed a text or unit of meaning. They also realized that the sum of the elements collectively meant something.

For

example, picking up on just one of the above elements of authoring,

Harste, Woodward and Burke observed in the scribbles of children from

families who had a first language other than English, some interesting

differences.

For

example, picking up on just one of the above elements of authoring,

Harste, Woodward and Burke observed in the scribbles of children from

families who had a first language other than English, some interesting

differences.

The writing below shows just how different scribble can be

for four-year-old children living in homes that speak different

languages; in this case, English, Arabic and Hebrew.

So, what does this mean for early writing?

Even though we've moved a great deal in family and school practices in the last 30 years, the following brief comments are still relevant and important for parents and Preschool teachers to understand.

I believe we need to:

- Take children's early drawing and scribble seriously - look at it, enjoy it, discuss it with your children (e.g. "What's this?" "What does this mean?" etc).

- Encourage children to write - give them blank paper and simply suggest they "write"!

- Let children see you writing and talk about your writing.

- Look for patterns in children's early drawing and scribble and expect to learn things about your child from it.

- In

short, encourage writing just as much as you encourage reading and

celebrate their drawing and 'writing'. How? Put it on the wall, fridge, notice board. Date it and

keep it, or make up a writers' folder etc.

I have also written about this topic at length in other publications such as my book "Pathways to Literacy", Cassell: London, 1995.

What's different since I first wrote about this topic over 25 years ago? And why does it matter?

a) The Differences

There are a number of key differences in 2023.

First, children are more likely to use devices for writing and drawing today. Early scribbles might be made on an iPad or similar device as well as on paper, walls, footpaths etc. And of course, most of these are rarely retained.

Second, adults should take early writing and drawing in any form more seriously. Look intently, ask your children to explain what they've written, drawn and so on. For example, the image below was drawn in 2007 and is one of my favourites from a grandchild who at the time was 4 years old. We'd been to the aquarium and he drew this back home and explained that he'd drawn it from the perspective of the fish. After he drew the image below he said, "that's how the fish looked at us while we were looking at them."

Third, children probably spend less time with parents in the earliest development phases (0-4 years) than they did 30-50 years ago; attending playgroups and childcare centres.b) The adjustments we need to make

Today, parents and teachers are far less likely to observe their children or students as they compose, whether in text or drawings.

As parents, we need to see iPads and other devices not just as a way to keep our children quiet, while we do other things. To be sure, there are times when we do NEED to do this. In days gone by the TV and toys played their part in achieving this, as did sand pits, parks etc (but let's not lose these either).

Above: A teacher using an iPad to demonstrate

My recommendation to parents (& teachers) is that when children are using devices, we need to ask them regularly what they're doing, and comment on drawings etc. You might even capture screen shots of special things to share with others (like parents, family etc). Create an electronic portfolio for toddlers.

Teachers of course can make much greater use of iPads and other devices in the classroom to encourage writing, drawing and far more. They are now tools that can be used individually or in groups. I have a graduate student Norah Aldossary who has just completed an interesting PhD on this titled 'The Potential of iPad Apps to support Vocabulary Development in Children Learning English as an Additional Language'.

Other literacy educators have been doing great work in considering how to use devices for learning in classrooms. For example, Michelle Neumann has written about this in 'Teacher Scaffolding of Preschoolers' Shared Story App and a Printed Book' (2019). The many studies by Michelle and others have shown varied benefits from using iPads in this more educational way. Some have found varied benefits, for example:

- Vocabulary benefits (e.g. Shang & Gray, 2014)

- Comprehension benefits (e.g. O'Toole & Kannsass, 2018)

- Word learning in 5 year olds (e.g. Korat et al., 2010)

However conversely, others have found that if used badly, devices might lead to poorer vocabulary and story comprehension (e.g. de Jong and Bus (2003). This seems linked to the children ignoring the text and 'reading' the pictures alone. I'd also suspect, this is linked as well to less child and adult interaction, which we know 'stretches' children's language and learning.

Another interesting study by Roskos, Carroll and Burnstein (2012) looked closely at how teachers used the iPads. They found benefits when teachers used the iPad to extend shared reading by asking questions, explaining word meanings and engaging the students in conversation as they read the iPad stories. This of course leads to development.

In short, as we live in times where the parent and child, or the teacher and her/his students no longer sit reading book stories like they once did with their children, the iPad has potential to facilitate play and experimentation with language and with it growth in language, reading and writing.

Summing up

Children's play always has been, and still is, very important for learning. While the world has changed as technology has developed, the importance of stories and the interaction of children with adults as well as other children, is a key factor in early learning. There is a freedom in play that encourages:

- Risk taking

- Experimentation

- Boldness

We must never allow our busyness, or the convenience of devices to reduce the place of play in children's early years, both prior to school, but also at school. This is a challenge that teachers and parents alike need to take on.